In the first part of this article, we described a little about another perspective of the use of grasses in agriculture. This time we want to share with you three other real-life experiences in Syntropic Farming that we had the privilege to see.

The idea of including the savanna element in the dynamics of a syntropic plantation was first tested in large-scale in some consultancies Ernst did for farmers in Mato Grosso (BR) and at Fazenda da Toca in São Paulo. In the latter case, Ernst was able to initiate and closely monitor several models. The species chosen was Panicum maximum, with the variety known as mombassa. Famous for its high biomass production, for tolerating a little shade and for its cespitose growth – that is, in clumps – it would be the first great “fertilizer factory of the system.”

The mombassa was broadcast in rows between the tree/banana lines. The width of this strip may vary, but usually is 5 meters, wide enough to mechanize the cut. The procedure is easy to understand. After mowing, the mombassa is placed (accumulated) in the adjacent tree line, half of the strip for each side, forming a double-row pile of biomass, having the tree line in the middle. Depending on the place, the grass holds eight cuts per year, which provides a constant and generous layer of organic matter. This management brings many advantages. The mulch prevents the growth of unwanted weeds and thus excludes the use of herbicides or any other weed control (organic or not). In addition, as it dries, it gets whitish, which reflects sunlight and therefore keeps the soil cooler, moister and full of life. Underneath this layer, trees shed their roots and participate in the decomposition of the straw, along with bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms capable of “drinking” water from the atmosphere. In this case, the system proved advantageous, especially during the year 2015 when the region faced the famous “water crisis.” The resilience of the consortium that included eucalyptus and banana – two famous “soil dryers” – proved what Ernst and Ana Primavesi always stood for: no plant dries out the soil. What dries the soil is monocultures (lack of stratification), herbicides, heavy mechanization (that compacts everything) and exposed soil.

There are, however, technological constraints. No machine on the market cuts and organizes the grass in one operation and, on top of that, light enough to avoid soil compaction. Ordinary bush or grass cutters do not make a clean and sharp cut – a precondition for a good regrowth. They usually do the opposite. They shatter the plant. The best ones are the mowers with frontal cutter bars. They make a clean cut, but do not organize it. Ernst is developing a machine. He dreams of a system with two sets of cutter bars. An upper one would cut and place the grass to the side using a belt. Another cutter bar would be 10 or 15 cm lower, providing some biomass to the grass itself. While the perfect machine does not appear on the market, some groundbreaking farmers have made remarkable tests that point the technology in a new direction.

Large-scale banana cultivation and grass – Martinique

Industrial banana cultivation suffers today from insurmountable challenges. Whether due to new diseases, depletion and soil erosion, or lack of workforce, farmers in the largest banana producing centers face an uncertain future. You can learn more about this subject here, here, here and here.

On a 400-hectare farm in Martinique – a small French island in the tropics (where part of the bananas that feed the European market are grown) – a father and son endeavor took a whole new direction. More than ten years ago, the farm suffered from erosion after many conventional cycles of sugar cane and banana cultivation. The soil was unstructured and annually washed down by the heavy rains that hit the Caribbean during hurricane seasons. As a preventive measure, Bertrand – the father – innovated by planting the grass brachiaria to fight erosion. The action was a huge success. The presence of the perennial species not only hold the land but also improved the soil in general, which allowed them to adopt better practices such as less use of inputs and pesticides. In 2016, Patrick – the son – invited Ernst for a consultancy, and since then we’ve been there twice to see their promising and innovative system.

Ernst suggested to include guinea-grass (mombassa) in the rows between the banana + tree lines, every 5 meters. With just over a year, the planting dynamics worked very well, albeit with many technological bottlenecks. The unfortunate hurricane Irma punished the region in 2017, taking down most of the plantations. A new area was done with some improvements, which included eucalyptus and new trees. As Martinique belongs to the European Community, it has facilitated access to a broader range of machines. We recognize and appreciate the innovative spirit of the farmers Bertrand, Patrick, and Romain (the manager). Since they got convinced, they are tirelessly testing and investing in new solutions for cutting and organizing the grass. They are already on the third machine, and their experience contributes significantly to our understanding of the challenges and possibilities of this model. We are very grateful for their determination (typical of pioneers), and for sharing the development of the plots with us.

Above, the first implement they used. Although an interesting solution, the heavy-weight tractor required to run it left a bigger damage to the recently cut grass, which affected its capacity to regrow.

The “Chinese toy” is a good and lightweight solution. The downside is that it can’t handle thicker clumps.

The current solution above is somewhere between the first two attempts. Until we don’t have a dedicated machine designed for that purpose, the farmers do their best do perform the task as good as they can. Here they found a good balance.

Combining bananas with trees and species such as grass makes all sense, especially in areas that are under hurricane threat (which will grow bigger as we mess up with the climate). It is either new or difficult to conclude that the softer the soil, the deeper the roots can descend. That literally ties them to the ground. It is also straightforward to understand that perennial species that are not stripped annually live long enough for their roots to travel farther and deeper. In the case of grass, it is especially impressive. Its vigorous root system opens the way for roots of other plants to go down. In addition, they make associations with free-living bacteria that fix more nitrogen than many leguminous. With the constant contribution of organic matter from the grass cutting and tree pruning, the natural tendency of this system is to have a continuous increase in soil fertility and complexity. That can also respond to hurricanes. As the soil gets more fertile and fluffier, the roots feel stimulated to travel down and thus become more resistant to the winds.

Grass between veggies

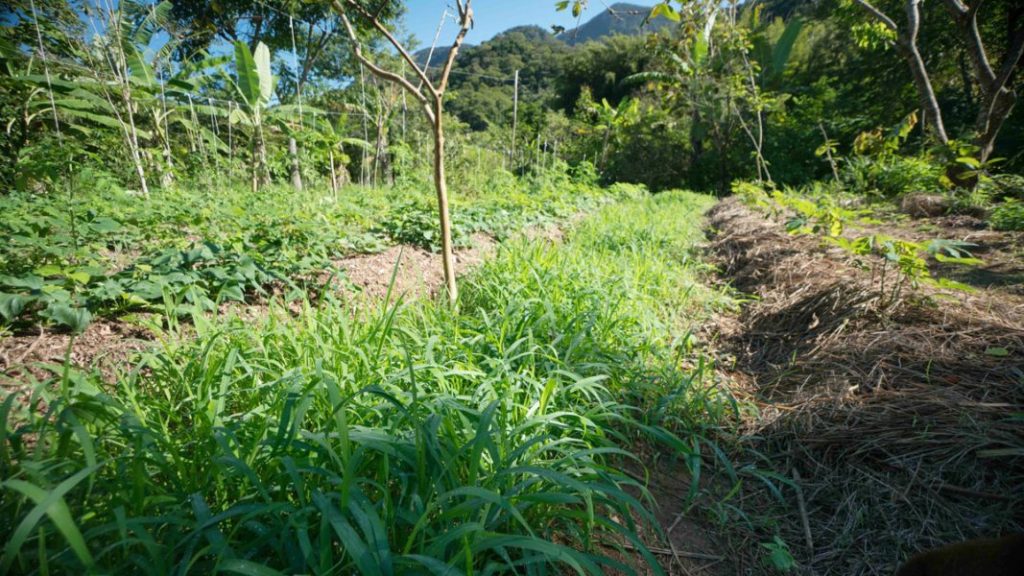

More recently, Ernst brought the use of grass even for horticulture. His decision to plant the mombassa in the middle of the beds would increase the total photosynthesis of the area, as well as preventing the growth of unwanted spontaneous weeds. The grass would fill all the spaces not occupied by the vegetables, and its transpiration would create a more humid microclimate on the surface of the plot, which reduces the need for irrigation. As in the examples above, the management is the clean-cut and incorporation of the leaves on the surface of the beds. With no room to grow, unwanted weeds would have little chance of thriving. Another advantage that we observed in Casimiro de Abreu (where Ernst performed the first tests) is that the grass stimulates the rooting of the vegetables. We did the trial, and the difference is impressive. It does not stop there.

There is a benefit of more subtle understanding. Weeding (a significant constraint of organic farming) is not only expensive but also follows an entropic logic that holds natural succession. Manual weeding, though less aggressive than chemical, is far from innocent. Pulling out the weed by the root promotes small wounds in the soil and exposes its most fertile and sensitive layer to the sun. Part of the microscopic life that began to accumulate in the rhizosphere dies instantly. The use of grass, though laborious, is syntropic. Instead of weeding, we benefit and prune the grass, which feeds and protects the soil. When the vegetable cycle ends, the bed begins to fulfill another purpose. Instead of a strip of bare, weary, twisted soil, the farmer inherits a fertilizer factory ready to provide food and protection to the surrounding tree lines.

It is also worth remembering that most of the areas that are now dominated by grasses were, one day, complex forests that we simplified. In almost 80% of the planet that we have cleared in the last 10,000 years, we lost concentration of matter and energy, we lost differentiation and we lost complexity. If we consider the desert and the forest as extremes, our agriculture has always operated in the counterflow of the planet, in degradation processes that begin in the forest and end in the desert. The latest technological developments have allowed an unprecedented increase in productivity, but have not yet reversed our path towards entropy. Every year, harvest after harvest, the planet’s soils are impoverished or eroded. Even with the super-harvests, we are still taking a step back – from forest to desert. Were it not for external inputs (from non-renewable sources), few soils in the world would still produce enough food to sustain large animals.

The planet visibly works differently – going naturally from desert to forest. Without our presence, even the most degraded land would once again be fertile through the slow process of natural succession. The concept of syntropy applied to crops proposes a new way of interpreting agricultural activities, favoring and driving life processes, synchronizing agrarian production with the inevitable flow of the planet. For that reason, we beg the organic farming movement to consider adopting perennials and natural succession as guidelines to become genuinely sustainable and regenerative. We can’t afford annual or biannual-monoculture-based diet anymore if we are serious about solving our environmental problems. That doesn’t mean we won’t grow lettuce or beans anymore. What we need to understand is that those species belong to the early stages of a long-term forest cycle and emerge after a forest clearing. We shouldn’t be allowed to grow short life-cycle plants alone. As well as any healthy organism, a forest needs all “cells” to complete its life cycle, from short-lived weeds to long-lasting trees.

The grass is just one example of how this perspective manifests itself in practice. Blaming grass or any other plant for soil impoverishment is unfair, wrong and sustain our war against life. Quite the opposite, it gives us a chance for redemption. Well managed, it is the natural capital we have available to take the system forward, accelerating natural succession toward more complex systems – the planet’s natural strategy (and a fertility-building machine). Modern agriculture is wasting the potential of grasses and many other species. The intelligent management of these plants depends on a change of point of view and technology. Making war on them does not solve the problem. Their occurrence is a consequence, not a cause. That explains why the use of herbicides in Syntropic Farming is neither forbidden nor encouraged. We design our systems in a way we don’t need to deal with that option. It’s an illusion to believe that fierce regulations or punishments will put an end to the abusive use of agrochemicals. What we need is to overcome our need for them. Fighting weed doesn’t make sense to us. As Ernst says, “I work with life. I grow my weed, and I manage my weed.”

Não sei se este equipamento tem um corte mais limpo, porém parece bastante leve.

http://www.bcsagri.it/en/product/mowers-537a868fa2387c44627b23c7/622-reaper-binder-55a60652fd6088c27af862ff