Agriculture is by far the most innovative and revolutionary activity humankind ever engaged. It shaped all corners of our existence and defined how we perceive the natural world. Through agriculture, we changed the planet in a way no species has ever done before, leaving our traces all the way from the high atmosphere to the bottom of the ocean.

In that sense, what we know about the history of farming shows us that the controversial debate around what made hunters and gatherers shift to agriculture is more speculative than concrete. There are different theories trying to explain what motived the first human settlements: adaptation to climate change after the last glaciation; a need to have a better access to food supply; an inevitable evolution of technology; the need to integrate individuals with physical limitation to hunt/gather; population growth (either as a cause or as a consequence); and there are also some hypothesis supporting that the desire to possess and protect assets also motivated those first settlements. Naturally, the most accepted scientific approaches see it as a process composed of many different variables acting simultaneously during a long interval of time.

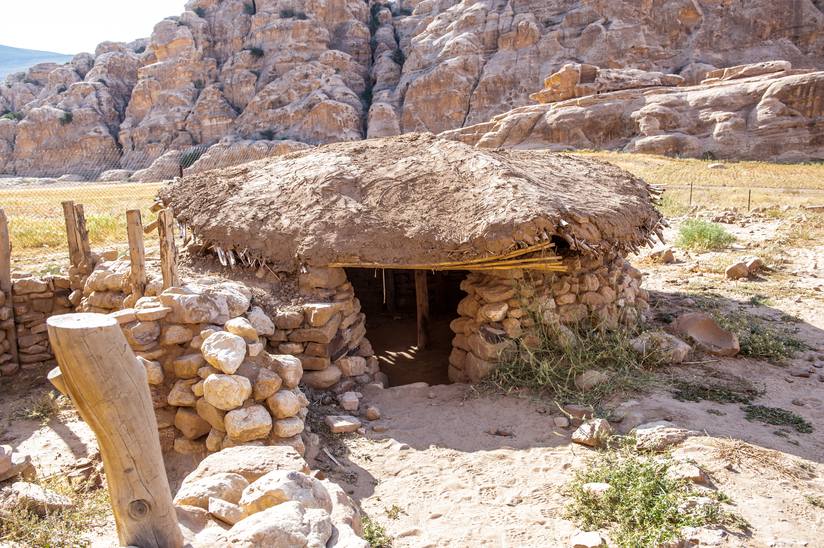

In the East, for example, the transition period from hunters and gatherers to proto-farmers took more than 1,000 years. The archaeological findings that sustain this fact are composed of traces of domesticated plants and animals, working utensils like scythes, axes and mills, ceramics for storage, as well as an evident evolution of housing constructions between 9,500 and 9,000 years ago. A certain level of demand for social complexity seems to be inseparable from the emergence of agriculture, so it is unquestionable its correlation with the changes in the ecological, social, economic, cultural and technological order.

Another explanation provided by archaeological findings tells what motivated the next technological transformation of agriculture: the one that went from a system of itinerant production to a system of permanent production. The fact that the new model is more laborious and less profitable seems to suggest that only a strong constraint could drive such change. In this case, the demographic pressure is the most likely hypothesis – but not without being associated with circumstantial ecological and technical limitations.

While itinerant agriculture uses “slash and burn” as the main technique, the permanent farmers begin to work with the plow and the fallow (resting period of land to guarantee the recovery of exhausted areas). The advantage, compared to migrant cultivation, would be the need for a smaller area with increased production proportionately.

For the researcher David Montgomery, who studies the emergence and decay of civilizations based on erosion traces left in the soil, the advance of the agricultural frontier is directly related to the ecological conditions which limitations were, at each step, placed a little further. In other words, firstly farmers took over top-quality land in regions with a good rainfall regime. When exhausted, especially after the development of irrigation, the agricultural activity migrated to good quality land without rain. With the invention of the plow, it was also possible to expand to not-so-good land or return to those already used. The direct result of intensive farming and goat herding has been the abandonment of entire villages in central Jordan about 6.000 BC, leaving behind a trail of soil erosion and degradation.

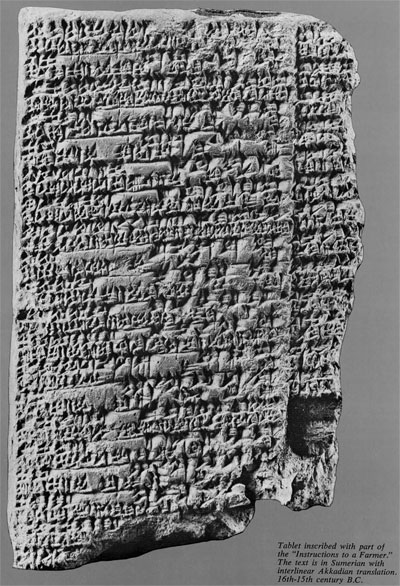

One of the earliest written records about agriculture is “The Farmer’s Instruction,” a sort of agricultural techniques manual from the Sumerians. Written as a farmer-orientated letter to a son, it cites the use of the plow along with a type of seeder, fallow technique, irrigation and the concern with salinization, and above all, any experiment is expressly discouraged. Innovation in agriculture is considered a risk a farmer could not afford.

These examples point us to two fundamental conditions of agriculture which made it not a fertile environment for innovation in either remote Sumerian reality nor in our modern society. Above all, the pattern is useful for our present time, since we are also on our ecological limit and we can not risk reducing production under the possibility of food shortages.

The history of agriculture shows that this activity is continuously fleeing or fighting the inexorability of nature. Farming always had to deal with the conflict between having to meet the urgent demands of the present and the responsibility for the future, which would mean prioritizing more sustainable practices.

The fact that we have overcome (or postponed) the impositions of nature over the course of these 10.000 years induces a certain belief or faith that the solution to the chronic environmental crisis will come exclusively through the technological path. Artificial intelligence, robotization, nanotechnology, or even the discovery of water on Mars come as a hope that a machine-god will solve all the great impasses without us having to change our social structures and models of production and consumption. This view ignores the fact that, as Lynn Margulis said, so far the only way we humans have proved our realms was by expansion. “We continue to be bold, arrogant and recent, even as we become more numerous.” We can not reproduce mechanisms of life and increment of natural capital that we have not yet been able to describe at all.

At the other extreme, we have those who advocate a return to traditional farming, and to a mythical pristine nature. However, we are living in a time when human activities, while not controlling nature (as professed by the Enlightenment ideal), actually determine all dimensions of ecological life. And despite the “back to land” movements of the 60s and 70s left an important legacy, they are also a well-known roadmap of convictions and boundaries.

When we study the history of agriculture using the perspective of syntropic farming, we suspect that a conciliatory solution between the return to traditions using new technologies may not be enough, since the paradigms that underpin the later were just the rationalities that brought us to the point where we find ourselves today: having to solve an ecological and a productive crisis.

We will not change the way we interact with nature while “integrated” or “ecological” or “sustainable” management is conditioned by technological constraints, legal coercion or social punishment. On the other hand, if we change our way of thinking and reposition ourselves as a species in the ecosystem – as syntropic suggests and operates – we have a chance to reroute and reconcile our agricultural practices with life on this planet.