There is no quick answer. We have to be honest and immediately warn that you won’t find a recipe ready to copy and paste here. Syntropic Agriculture (also described as successional agroforestry) is not a technology package that can be purchased, nor a definitive design plan that fits all tastes. It is first and foremost a change in perspective. It’s a new proposal for reading the ecosystem which enables the farmer to seek his/her answers using another reasoning, quite different from what we’re used to.

Syntropic Agriculture is constituted by a theoretical and practical setting in which the natural processes are translated into farming interventions in their form, function, and dynamics. Thus we can talk about regeneration by use, since the establishment of highly productive agricultural areas, which tend to be independent of inputs and irrigation, results in the provision of ecosystem services, with special emphasis on soil formation, regulation of microclimate and the favoring of water cycles. That way, agriculture is synced with the regeneration of ecosystems.

Instead of recipes, there is a set of concepts and techniques that enable the understanding of Syntropic Agriculture’s fundamental characteristics. Its creator, Ernst Götsch, bases his worldview on a transdisciplinary scientific approach and a practical daily routine for more than five decades. The logic that guides his decision-making process follows a path that arises from Kant’s ethics and crosses physics, Greek philosophy, and mathematics. It also relies on biology, chemistry, ecology, and botany, and incorporates the current technological scene, adapting techniques and tools from other areas. Ernst Götsch’s agriculture relies on a coherent and systematic chain of data, free of internal contradictions, which not is not only sustained by a logical narrative but also includes a practical and concrete expression at the end. From planning to planting, there is a method, and there is a practical result. More than a good idea, Syntropic Farming has proven to work, and it can address the biggest social and environmental challenges of our time. Read below the article in which Ernst describes the 15 principles that serve as Syntropic Farming’s fundamental guidelines.

Peculiarities of Syntropic Agriculture

Many of the sustainable farming practices are based on the logic of input substitution. Chemicals are replaced with organic, plastics with biodegradable materials, pesticides with all sort of preparations. However, the way of thinking is still very close to that one they oppose. In common, they combat the consequences of the lack of adequate conditions for healthy plant growth. Syntropic Agriculture, on the other hand, helps the farmer replicate and accelerate the natural processes of ecological succession and stratification, giving each plant the ideal conditions for its development, placing each one in their “just right” position in space (strata) and in time (succession). It is process-based agriculture, rather than input-based. In that way, the harvest is seen as a side effect of ecosystem regeneration, or vice versa.

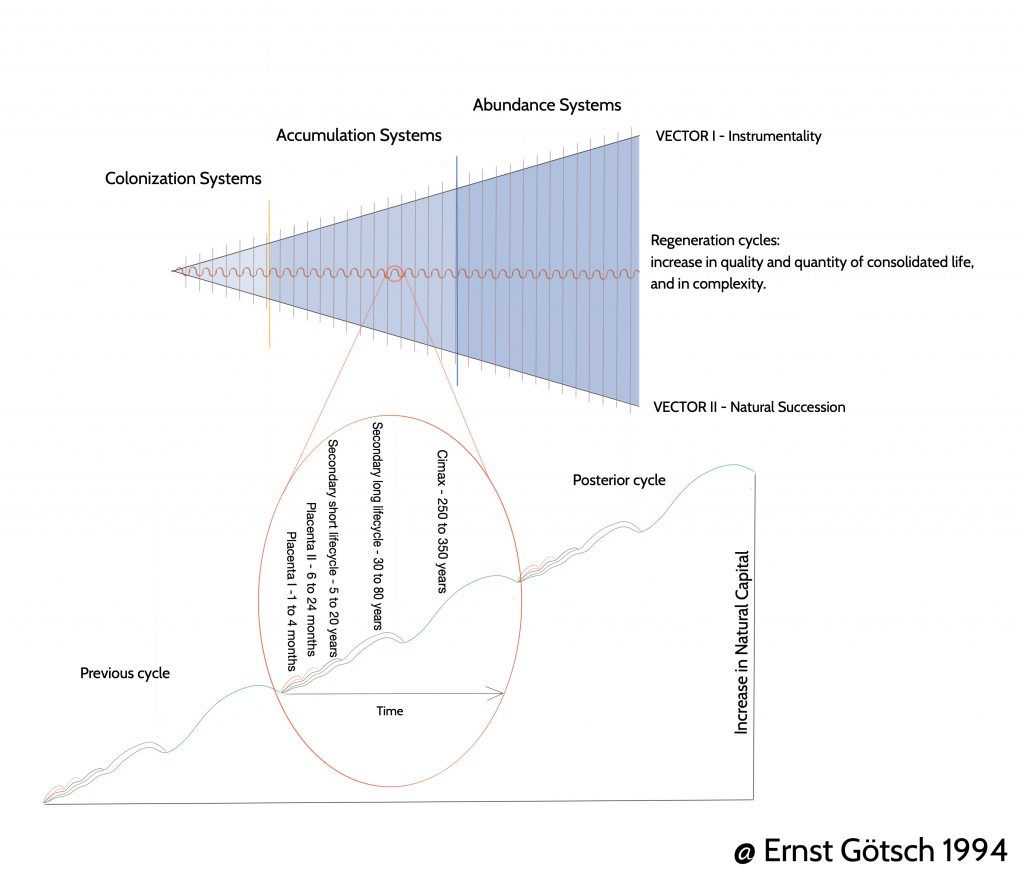

“Corn is emerging, short-life cycle, belongs to placenta of Abundance Systems.” This type of sentence is common among farmers who work in Syntropic Agriculture. They refer to any species mentioning at least these four categories – the fundamental criteria that must be observed in the orchestration of syntropic crops. Space (stratification) has to be harmonized over time (life cycle), respecting the successional steps (Placenta, Secondary and Climax) within each of the Systems (Colonization, Accumulation and Abundance), according to Ernst’s definitions. A syntropic agroforestry, therefore, evolves and transforms over time and space, always “towards the increase of quantity and quality of consolidated life”, says Ernst.

What is Syntropy?

It’s very easy to say that we want to work with nature and not against it. But which nature are we talking about? What reading and interpretation do we make of this observed nature? This is one of the main differentiating points of syntropic agriculture. And in the heart of its understanding is the concept of Syntropy.

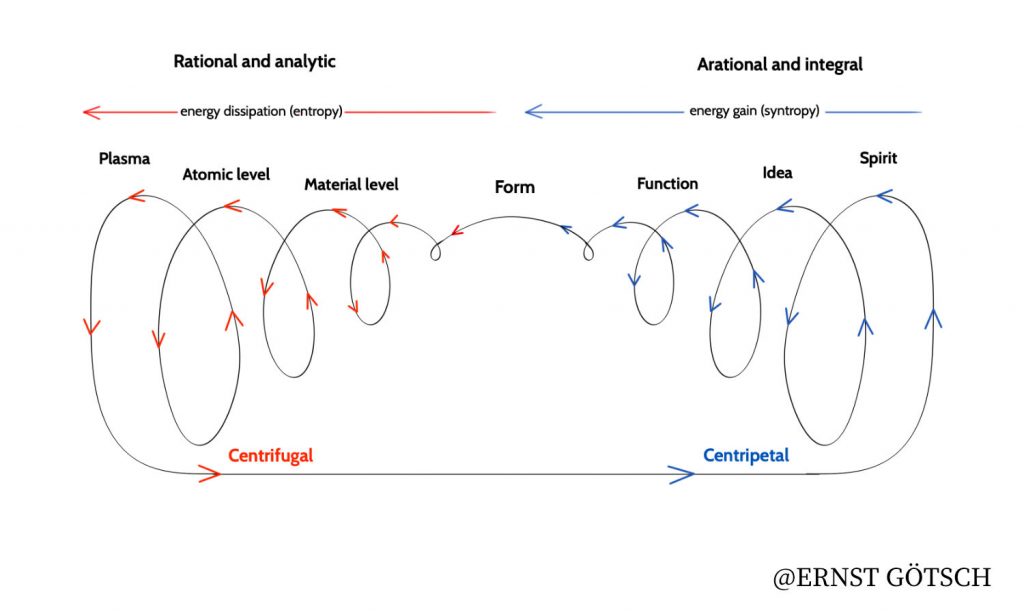

We are more familiar with the thermodynamic concept of entropy, which refers to the disorder-related function of a given system associated with energy degradation. Everything about energy consumption and dissipation is therefore explained by the Entropy Law which governs the physical world. But it is not recent that the inapplicability of the Entropy Law is discussed to describe what happens in the biological world. In trying to bring the concept of entropy into dialogue with living systems, great scientists concluded that there was a need to describe a complementary tendency. For the mathematician Fantappiè (1942), if on the one hand entropy has brought the understanding that all concentrated energy in the universe tends to dissipate, simplify and dissociate, syntropy manifests itself by forming structures, increasing differentiation and complexity, as with life. That is, while the entropy disperses, syntropy concentrates. Without using the term “syntropy”, physics such as Erwin Schrödinger also reaches a similar conclusion in the 1940s: “life feeds on negative entropy”. The idea that there is some opposite or complementary force to entropy – and that life on planet Earth would be the manifestation of that force – has intrigued scientists from a variety of fields, such as Albert Szent-Györgyi (chemistry), Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (economics), Viktor Schauberger (Natural Sciences), Ulisse di Corpo & Antonella Vaninni (psychology), and, as early as the 1970s, would help compose the premises of Lovelock and Margulis’s Gaia Theory.

Syntropy and Agriculture

Ernst Götsch’s visual representation of energy flow during the dispersing phase (entropy) and the converging phase (syntropy).

Bringing the concept of syntropy into agriculture, Ernst Götsch introduces an unprecedented perspective associated with this practice. He understands that, in the context of the ecosystem, there are not only dissociative but also complexifying processes. The collective metabolism of organisms reorganizes entropic residues into more complex compounds. This would be the mechanism by which life thrives, always generating, according to Götsch, a positive energy balance both in the subsite of the interaction and on the planet as a whole. So when we say that we want to work for nature and not against it, that is what we are talking about. Having syntropy as a fundamental matrix for the interpretation and management of cultivated landscapes is what supports the regenerative capacity of syntropic agriculture.